On rapid prototyping and reverse engineering in my work

I use AI to prototype rapidly, not to finish things faster, but to open up visual and conceptual space. A single prompt, especially one drawn from museological or archaeological language, might generate dozens or hundreds of image variations. I scan for what I call a sweet spot—a slippage, a visual rupture that hints at something partially formed or disturbingly familiar. AI lets me surface patterns, catch deviations, and push them further. It’s not about resolution. It’s about resonance.

Once I find something with potential, I reverse engineer it. I imagine how it might have been made, what material logic it suggests, what speculative ritual it belonged to. I remake these images in copperpoint, mosaic, or cast forms, treating them as artifacts from an invented but believable past. It’s less about generating images and more about reconstructing speculative memory through tactile labour.

I’m interested in how AI, especially in the form of deepfakes and simulated imagery, is shaping not just aesthetics but history itself. But this isn’t new. History has always been unstable. Archives have always been biased, written by victors, sanitized by institutions, censored through omission. What’s different now is the speed and fidelity of the simulation. AI doesn’t invent historical distortion; it just renders it faster, more believably, and at a massive scale.

My work asks: Who owns history? Who gets to write it? What happens when memory is automated, when the record becomes an output? AI doesn’t just remix the past. It produces convincing false histories. It gives visual form to erasure. And that makes it dangerous, but also revealing. I use it to expose the instability that has always been there.

I treat AI like a flawed historian, a hallucinated archive. The outputs I receive aren’t definitive. They’re unreliable narrators. That’s what makes them worth engaging. Through selection, translation, and material intervention, I reclaim authorship. I’m not collaborating with the machine. I’m interrupting it. I’m curating a body of work that could be misread as recovered, but in fact, it’s constructed, layered with doubt, fiction, and the politics of remembering.

by Jennifer Tazewell Mawby

References:

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1981.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Foster, Hal. “An Archival Impulse.” October 110 (2004): 3–22.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. W.W. Norton, 2019.

Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” In The Wretched of the Screen. Sternberg Press, 2012.

Warburg, Aby. The Mnemosyne Atlas. Various translations and editions.

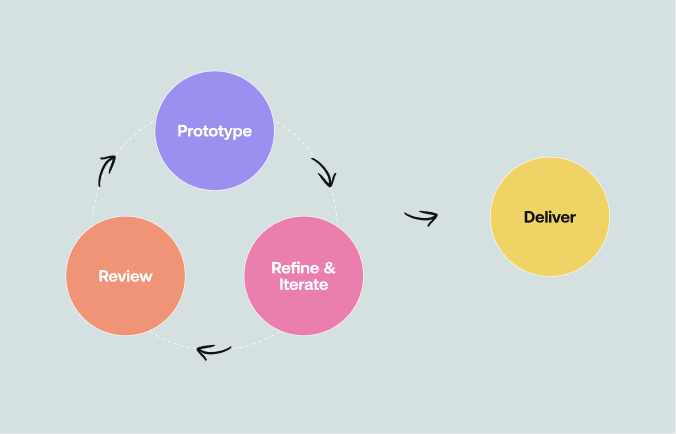

Rapid Prototyping illustration courtesy of Muse Mind Agency.