The Politics of Simulation

Simulation is never neutral. It is a performance of coherence, often mistaken for truth. In the digital era, images do not document. They generate belief. AI-driven simulations, from deepfakes to fabricated artifacts, do not merely mimic reality; they reshape it, faster and more convincingly than ever before.

But this isn’t new. History has always been unstable. As Jacques Derrida wrote in Archive Fever, the archive is never simply a record; it is a system of power, memory, omission, and desire. What we accept as history has always been curated, biased, and contested. AI does not invent historical distortion. It renders it more efficiently, more believably, and at scale.

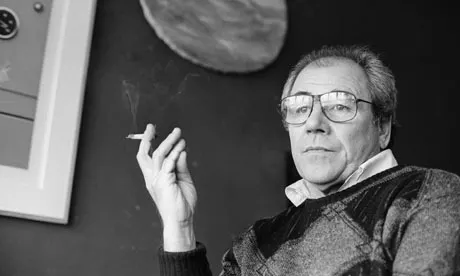

Deepfakes are simply the latest evolution of what Jean Baudrillard described as the “third order” of simulation – a state where reality is replaced by its image, and the distinction between original and copy collapses. We are no longer looking at the past. We are looking at a version of it that never was.

In my practice, I work with AI not to generate style but to access these fractures. I use prompts drawn from museological description and archeological cataloguing, a language that already carries the weight of historical authority. The machine returns hallucinated fragments, speculative forms that feel half-remembered. I treat these as unreliable documents, and then retranslate them by hand, into copperpoint, mosaic, or cast materials. The results are not reconstructions, but speculative artifacts.

I’m interested in what Hal Foster calls the archival impulse, a way of using fragments and ruins not to restore the past, but to disrupt it. My use of AI is less about invention and more about recursion, about surfacing visual patterns that span centuries. This process, for me, is deeply material. The digital output is not the end. It is the invitation to begin.

Simulation, in this context, becomes a political question: Who owns history? Who gets to write it? And what happens when machines start writing it for us? As Hito Steyerl argues in In Defense of the Poor Image, digital images often conceal the conditions of their own production—compression, circulation, omission. My work tries to hold those conditions visible, even as it plays with the aesthetics of decay and erasure.

I use AI not because I believe in its vision, but because I don’t. I treat it like a flawed historian—a system that makes beautiful errors. What it gets wrong is often more revealing than what it gets right. Through selective intervention, I reclaim authorship. Not to correct the machine, but to interrupt its authority.

We do not need to restore the truth. We need to remain inside the fracture. That is where memory can be questioned, reshaped, and perhaps reclaimed.

By Jennifer Tazewell Mawby

References

- Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1981.

- Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Foster, Hal. “An Archival Impulse.” October 110 (2004): 3–22.

- Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” In The Wretched of the Screen. Sternberg Press, 2012.

Photo credit of J. Baudrillard pending.